Thread I span. Thread I measured. Then, I cut.

And wove the measure span into the tapestry of life

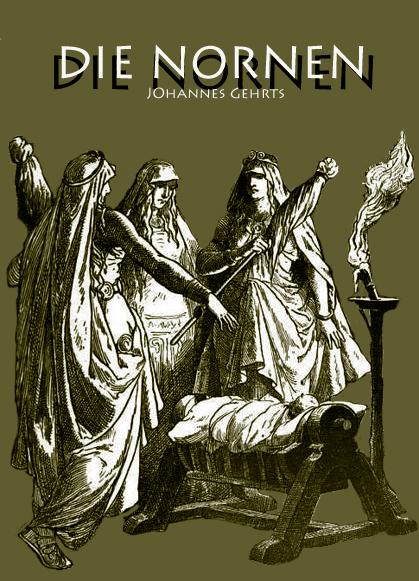

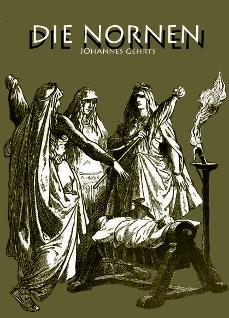

The Norms from a lithograph by Johannes Gehrts

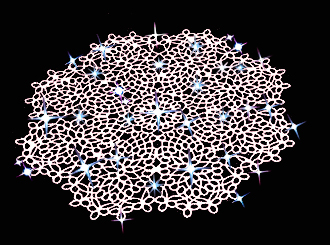

The idea of tapestry knots

holding memories came from something half-remembered about how the

Incas used knots to write.

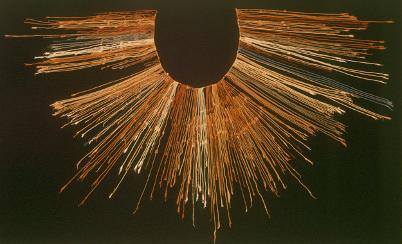

These are called Quipu or talking knots. Lengths of knotted strings we are still unable to read.

In a culture as ancient & global as the fairy

race, largely ruled by women, it seemed only logical to choose traditional weaving

skills as a method for the fairy queens to make maps and keep racial memories alive.

Inca Quipu courtesy of Wikipedia

No one has any idea when weaving started. Perhaps it

originated long before we were even human. Chimpanzees loosely weave branches

and leaves into sleeping platforms in the trees. It is likely early humans wove

baskets, not only to carry goods but also to fish. A fishing net made from

willow is known from 85,000 years ago, while the first evidence of textile

weaving is a 70,000 year old fabric impression.

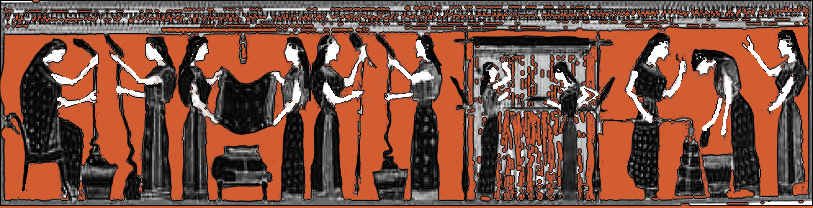

Spinning and weaving came under the provenance of women’s magic. In cultures where men wove, such as ancient Egypt, they are believed to have usurped the woman’s traditional role. Neith, the Egyptian goddess of weaving, was viewed as an ancient mother to who the other gods went for advice, and one who provided mighty aid in war. This attribute resurfaced some two millennia later with the powerful Norse goddess Freya, whose name simply means ‘The Lady’, and her sorceress representatives, the Volva.

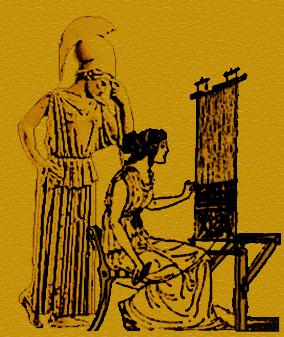

In Ancient Greece and Rome, women’s skills were

denigrated, except for goddesses too ancient and powerful to ignore. Goddesses

such as Athena the founder of Athens. While not a goddess of weaving, Athena was

so proud of her skill at the loom she turned Arachne into

a spider when she bested her in a weaving competition.

Penelope, the faithful wife of Odysseus, refused to believe her husband was dead, even though it took him ten long years to return from the Trojan War. Forced into agreeing to remarry when her tapestry was complete, she spent every night unpicking the threads she wove during the day.

In the dark ages before Dorian invasion of Greece, primeval goddesses, such as the Graeae, the Muses, the Furies and the Moirai occupied a shadowy place in the minds of men. Each group of goddesses were originally three sisters, suggesting they are revenants of the original triple-faced Moon goddess. The Moon has three faces. The new moon, representing the virginal bride, the full moon symbolising the fertile mother and the old moon representing the old woman whose job it was to prepare the tribe’s dead for burial.

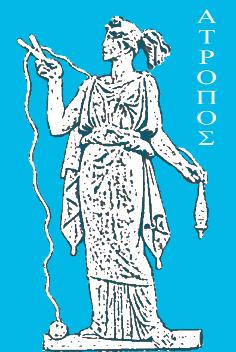

The three Morai or Fates appeared three nights after a

child’s birth to determine its fate. The sisters doled out the thread of life,

wove destiny into the world tapestry and in the end cut you dead.

They were: Clotho meaning the spinner; Larchesis- the measurer (who allotted the length of life) and the small but terrible Atropos, (the name means ‘inevitable’) who cut the thread when life was done.

As Norse myth claimed the gods came from the east, following the River Danube through the Black Sea from Byzantium, it is no surprise the Moirai are echoed in the three Norns. The origin of the word Norn may come from the verb ‘to twine’. The sisters are named from the verb ‘to be’. Wyrd- means both fate and the past tense - what was; Verdandi is the present tense- what is; Skuld is the future- what will come to pass, with an additional sense of ‘a debt to be paid’.

In Norse culture, magic and weaving were intimately linked with Seidr (sorcery); elf magic. Although seidr was practiced by both sexes, it was considered unmanly. It left men cowardly, concealing, duplicitous and clever with their tongues, instead of forthright, open, reckless and brave. During Christian times, seidmenn were often put to death by being tied to rocky outcrops at low tide and left to drown. On one occasion a group were burned alive inside a house by the king.

Greatly admired and feared were the travelling sorceresses called Volva. Often they were assisted by local women singing and dancing in circles at their rituals. Julius Caesar was the first to mention aged women dressed in white, who sacrificed prisoners of war and sprinkled their blood in order to make prophecies.

The Volva’s most powerful magical instrument was a wand or a distaff, a long spindle used before spinning wheels to spin thread. Like the Norns, Volva could spin out a thread to bind a man, seducing and reducing him to illness. This suggests the sorceress, like a spider, could suck men dry of virility (from the Roman word vir: manliness).

Wives had a big a part to play in war as Volvas. Unlike the Celtic wife who often accompanied her man into battle, Norse wives stayed at home literally weaving spells on the loom to paralyse an enemy by tying him in knots, or free her husband from other women’s spells by loosening the weave.

taken from The Collected Essays of Horatio Grin